A Van Gogh masterpiece, a world-renowned museum, and a family’s decades-long search for justice collide in a courtroom battle that exposes the shadows still cast by Nazi art looting nearly a century later.

Story Snapshot

- The heirs of a Jewish family are suing New York’s Met and a Greek foundation, claiming Van Gogh’s “Olive Picking” was stolen by Nazis and later sold under suspicious circumstances.

- The Met’s own former curator was an expert on Nazi looting, intensifying questions about how the painting’s past was handled.

- Institutions face mounting pressure to revisit provenance and restitution of art with Holocaust-era gaps.

- The lawsuit reignites global debate over museums’ ethical responsibilities and the unfinished business of Holocaust-era theft.

When Art, Atrocity, and Accountability Collide

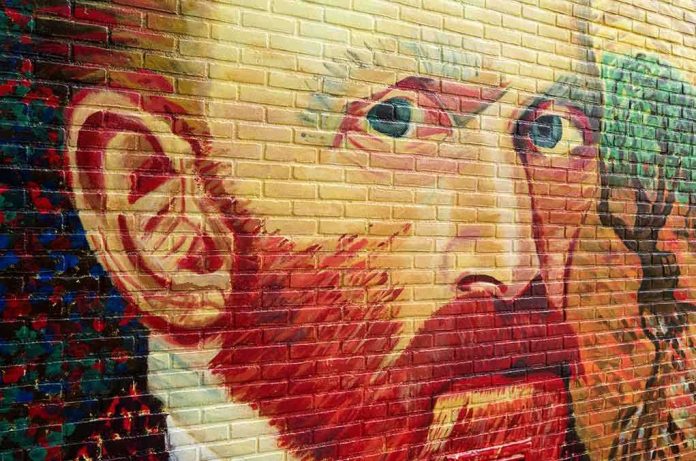

Vincent van Gogh’s “Olive Picking” hung for years in the halls of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, admired by countless visitors. Few could have guessed the painting’s journey included a forced sale orchestrated by the Nazi regime and a family’s exile from their home in Munich. The Stern family, prominent Jewish collectors, were stripped of their treasures as they fled Germany in the late 1930s—barred from taking prized works like Van Gogh’s landscape, which the Nazis declared “German cultural property.” The painting’s fate, like that of so many looted artworks, became obscured by war, bureaucracy, and the shifting priorities of powerful institutions.

After the war, “Olive Picking” surfaced on the international art market, passing through several hands before landing at the Met in 1956. The museum paid $125,000 for a work that, according to the Stern heirs, bore the unmistakable scars of forced dispossession. The Met’s acquisition and subsequent sale of the painting in 1972 to the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation in Athens are now at the heart of a landmark lawsuit. The heirs argue that both the Met and the Greek foundation either ignored or concealed the painting’s troubled provenance, continuing a long tradition of institutions prioritizing prestige over justice for Holocaust victims and their families.

The Lawsuit That Could Change the Rules

The Stern heirs’ case, filed in federal court in October 2025, is more than a quest for a lost painting. It’s a test of whether major museums and private foundations can be held to account for the ethical blind spots of the past. The plaintiffs allege that the Met, despite employing a curator renowned for his expertise in Nazi art looting, failed to heed obvious warning signs about the painting’s origins. They claim the painting’s sale involved deliberate efforts to obscure its ownership history, with Nazi authorities appointing a trustee to liquidate it and seize the proceeds. For the heirs, the painting’s journey is not just a matter of paperwork, but a symbol of the broader failure to reckon with the moral aftermath of the Holocaust.

The Met, for its part, has defended its actions, stating it had no record of the Stern family’s ownership during its stewardship of the work and that key information surfaced only decades after the painting had left its collection. The Goulandris Foundation, now the painting’s custodian, faces accusations of similarly failing to clarify the painting’s provenance and location. The dispute highlights the difficulty of unraveling the truth behind art that changed hands under duress, especially when records were lost, destroyed, or deliberately hidden by those seeking to profit from tragedy.

Why Provenance Research and Restitution Still Matter

This lawsuit is not an isolated incident. It joins a wave of legal actions and public debates challenging how museums and collectors address the toxic legacy of Nazi art theft. The provenance of thousands of works remains in doubt, and the art world’s willingness—or reluctance—to investigate these histories has real consequences for survivors, their heirs, and the credibility of cultural institutions worldwide. For many in the Jewish community and among Holocaust restitution advocates, such lawsuits are less about financial gain than about historical justice and the recognition of suffering that persists across generations.

Legal experts and art historians point to the complexities of proving ownership decades after the fact, complicated by international law and shifting standards of evidence. Yet the moral imperative remains clear: museums and foundations must do more than pay lip service to transparency and restitution. The Met’s current predicament, as well as the Goulandris Foundation’s, serves as a warning that the art world can no longer afford to ignore the provenance gaps left by one of history’s darkest chapters.

The Stakes for Museums, Families, and the Art World

As the lawsuit moves through the courts, the implications ripple far beyond a single Van Gogh. Restitution cases force museums to confront uncomfortable questions about their collections, their past acquisition practices, and their public trust. If the Stern heirs prevail, other families may find new momentum to pursue claims, potentially reshaping the art market and the way institutions approach their own histories. Museums may accelerate provenance research, disclose more about their holdings, and face increased scrutiny from donors, visitors, and lawmakers alike.

The Sterns’ legal fight is a reminder that the wounds of the Holocaust remain raw, and that the pursuit of justice—however delayed—can still bring to light the hidden stories behind the world’s most celebrated works of art. As the art world watches, the question lingers: can institutions built to preserve beauty also acknowledge the ugliness in their own histories, and will the next generation of curators and collectors finally close the chapter on Nazi-looted art?